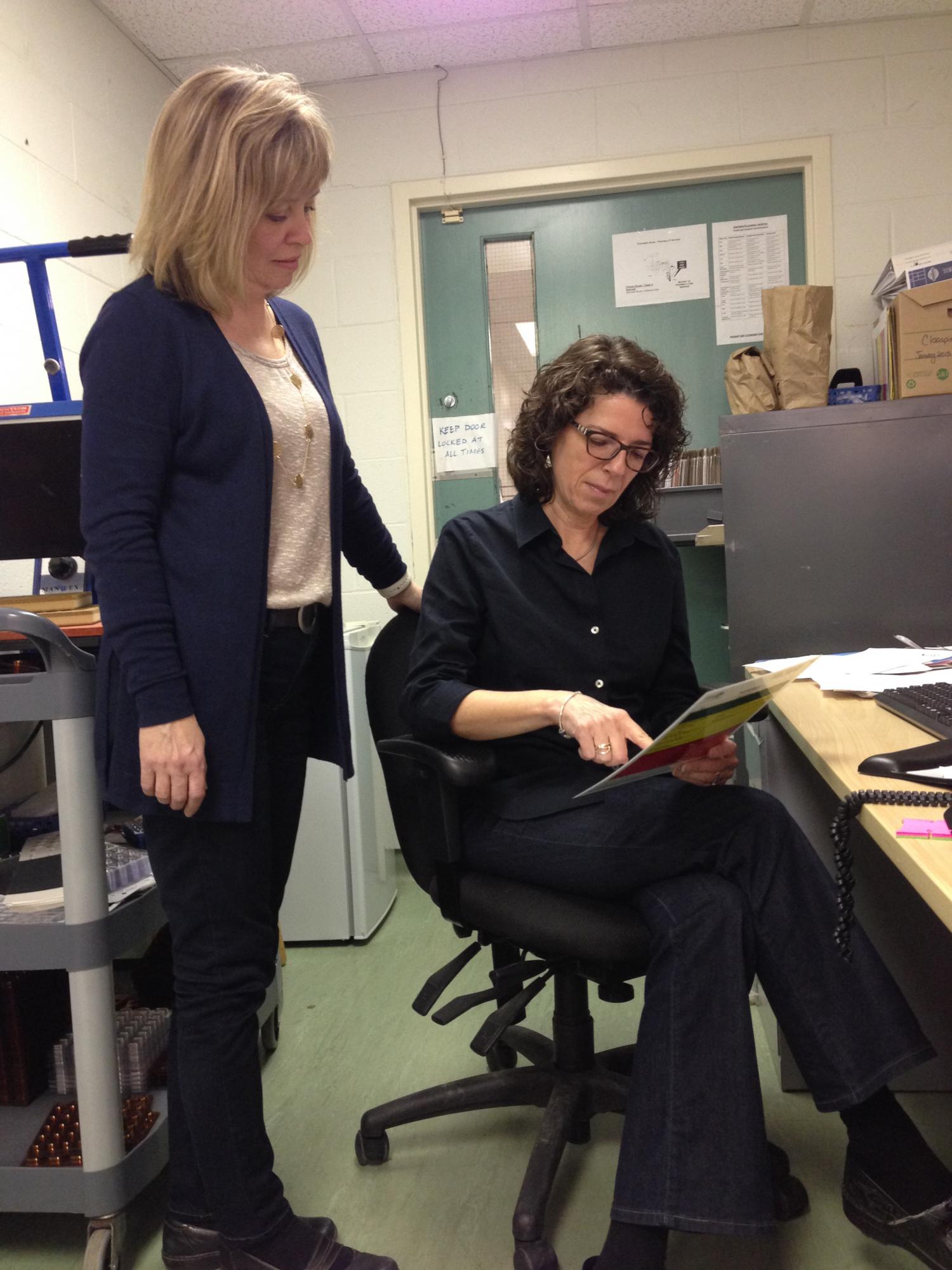

Pharmacist Kelly MacIsaac and pharmacy technician Karen Leyte’s partnership has existed for more than 20 years. The pair started working together at the Nova Scotia Hospital and the partnership continued at the Dartmouth General Hospital three years ago when the pharmacy department was closed at the Nova Scotia Hospital.

One of the main programs they work together on is the Provincial Clozapine Program. To fully understand the importance of Kelly and Karen’s partnership, a brief background of Clozapine is required.

Clozapine was introduced into the Canadian market in the 1960s. Initially it was used to treat depression. Soon, it was discovered that it had antipsychotic properties and doctors began to prescribe the drug for Vietnam Vets who were suffering from flashbacks and PTSD. A number of sudden deaths attributed to this drug resulted in the medication being pulled from the Canadian market. Research found the drug could destroy a patient’s white blood cells.

The drug was also found to be highly effective for patients suffering from schizophrenia and was reintroduced in the late 80s as a “third resort” for schizophrenia patients.

The reintroduction of Clozapine into Canada brought with it strict regulations. There are a number of steps that must be taken for a patient to access this potentially dangerous medication. A patient must have tried other methods of treatment with no success. A psychiatrist must complete paperwork explaining why the patient should receive the drug. Once approved, the patient must then be registered with the manufacturer of the drug and have frequent blood work to make sure their white blood cell levels remain adequate.

When a patient first starts Clozapine, they must get blood work done once a week. At the six-month mark, if the patient’s levels are still at an acceptable level, he moves to getting blood work every two weeks. After another six months, he can move to getting blood work done every four weeks as long as he continues to maintain satisfactory white blood cell counts. If the patient’s blood cell count changes, and puts the patient into the caution zone, they are required to have their blood work done twice a week until the counts stabilize. If their blood comes back in what the health care professionals refer to as the “red zone” then the patient must have another blood test within 24 hours. If they are still in the “red” they must cease taking Clozapine.

As the clinical pharmacist for the program, Kelly is responsible for reviewing applications from across the province that doctors submit to the program on behalf of the patient. The medication is covered under a provincial government high cost drug program for most patients taking the medication in Nova Scotia. Many patients with schizophrenia are diagnosed in the prime of their lives – late teens or early twenties. Depending on the severity of their illness, they may not be able to attend school or work so they may not qualify for their parents' medical plans or have their own coverage.

Kelly is responsible for reviewing the applications to see if the patient meets the eligibility criteria for the program.

Once the patient is approved for the program and is registered with one of the drug manufacturers’ national registries, Karen, along with two other pharmacy technicians, begins the process of monitoring the patient’s blood work. If the patient is late for his blood work, Karen contacts the patient, a family member or caregiver to investigate, and to remind the patient to get their blood work done. The medication is prepared and dispensed at the pharmacy at Dartmouth General, so if a patient is late getting his medication, Karen or one of her colleagues, follows up. Patients get their medication in an amount corresponding to the interval in which they get their blood tested: one week, two weeks, or four weeks.

It is required that patients have current bloodwork before clozapine is released but exceptions are sometimes made for a small supply to be given in order for the patient to have the blood work done and avoid a break in therapy.

If the patient’s blood work comes back in the “yellow” caution zone or the “red zone” the health care professionals and the patient are notified immediately.

Some patients come to the pharmacy at the Dartmouth General to get their medication so Karen and Kelly get to know them well and can see their progress. Other patients in the Halifax area receive clozapine with their other medications through their retail pharmacy but the clozapine is usually prepared and blood work monitored at the Dartmouth General Hospital. To maintain the safety of the system, the retail pharmacy must confirm that blood work has been done before it is dispensed to the patient.

“I have seen some Clozapine miracles,” says Kelly.

Her compassion for her patients is evident as Kelly recalls one patient who used to come to the pharmacy with his mother to get his Clozapine. The patient did not speak or make eye contact and was very paranoid. Eventually, he began coming to the pharmacy by himself.

“One day when I was coming into work he held the door open and spoke to me,” recalls Kelly. “He was eventually able to go back to university.” This was significant progress for the patient.

As patients get better, Karen can help them participate in activities that they would never have been able to consider prior to taking Clozapine. The ability to travel is very important for many patients. Karen had one patient who wanted to visit Florida for an extended period of time. This meant taking a supply of the drug with them and finding a lab in Florida to do his blood work and then fax the results to the Dartmouth General. She also helps coordinate a supply of medication and appropriate monitoring for individuals that move away from the Metro area. Many patients are living healthy and productive lives because of this medication, but they must still be monitored to ensure their white blood cell counts stay at a healthy level.

It can be heart breaking when a patient achieves success on the medication and then their blood work falls into the “red zone”. When this happens it is all hands on deck. Karen recalls one patient who had been on Clozapine and was starting to get well. When his blood work came back in the “red zone” she contacted Kelly right away. When patients are sick, they sometimes do not recognize their symptoms as part of an illness and may be paranoid. As they get better they may start to gain insight into their illness. This was one of those patients.

“As he started to get better, he began to ask more and more questions about the medication,” says Kelly.

He had become engaged in his health care and, after coming so far, it looked like he was going to have to stop taking Clozapine. Sometimes another medication can be added to the patient’s regimen that can help boost the white blood cell count but it is not always successful.

Kelly called the patient’s psychiatrist to discuss the options and they agreed to move forward with trying an additional medication. The patient took the medication and the whole health care team held their breath as they waited for blood test results to see if the drug had worked. It was successful and they were able to keep him on Clozapine. The patient continues to do well and is now attending university.

The success of the Clozapine program depends on these strong partnerships and teamwork between pharmacy technicians, pharmacists, and doctors. With currently 567 patients enrolled in the Nova Scotia Clozapine program, every member of the team plays a vital role.

“It’s a lot of work but it’s worth it,” says Karen.

Karen and Kelly get to see, first hand, the positive outcomes of the drug therapy.

“We feel privileged to be a small part of the success stories,” say Kelly and Karen. “That is the best part of our work. Clozapine can be life changing. It turns individual’s lives around.”