It's a lot of responsibility to be on one man's shoulders, but pharmacist Christopher Daley is responsible, along with his colleagues, for keeping about 800 of Nova Scotia's transplant patients alive and healthy. He is the Clinical Pharmacy Coordinator for the Multi-Organ Transplant Program (MOTP) in Atlantic Canada.

Chris is a busy man. He is also the Director of Clinical Research for MOTP, Strategic Lead for Research and Education for the Nova Scotia Health Authority, an Adjunct Professor at Dalhousie's College of Pharmacy, Chairs the Pharmacist Group for the Canadian Society of Transplantation, and is a member of the Atlantic Transplant Advisory Council.

Chris didn't start his pharmacy career with transplantation as his area of practice. After his post-doctoral advanced residency in critical care and cardiology, he worked primarily in critical care areas ,but when the opportunity in Halifax came up, he jumped at the chance because of the opportunity to work directly with patients and make a significant positive impact on their lives.

The patients Chris helps may have received a kidney, liver, pancreas or, sometimes, a heart. Lung transplants are not performed in Nova Scotia. He also has patients who are waiting for these organs. To get a kidney, a patient must be on dialysis, or very close to requiring renal replacement therapy. To get any of the other organs, patients must be dying . The one exception is pancreas transplants. Organ transplants are a last resort.

As you can imagine, organ transplants are not straight forward. They are also a relatively new medical procedure. Organ transplants have only been performed since the 1960s so there is still a lot unknown factors surrounding them. Each patient is so uniquely different that Chris must develop medication "cocktails" individualized for each patient.

"Once a patient receives a transplant, the only thing keeping them alive is their drugs," says Chris.

Immunosuppressant drugs, or what are commonly referred to as anti-rejection drugs, must be taken in the right amount and at the right time to prevent the patient's immune system from attacking the new organ, which the immune system sees as an invader. The patient's immune system must be suppressed to prevent this from happening, but not reduced to the point in which it can't fight bacteria and viruses that would otherwise make the patient quite sick or even kill them. There is delicate balance which takes time to establish. These medications must be taken for the rest of the patient's life, or until graft failure. Chris has some patients who were among some of the first transplant patients, getting their kidneys in the 1960s.

Chris works collaboratively with the patient and the rest of the health care team (including physicians, nurses, psychologists, and social workers) to ensure they have long and healthy lives. At the very least, patients visit the post transplant clinic once or twice a year, others much more frequently if their health is not stable, where Chris monitors the patient to ensure they are reaching their goals.

Chris ensures patients are fully educated on their condition and have access to their life sustaining medications. His enthusiasm and passion for his profession is infectious.

Every day is different for Chris. It brings new challenges and new opportunities to help his patients. Unique situations arise all the time and, without a lot of a studies available for reference on many of these unusual transplant issues, being able to recognize patterns and problem solve is key. When a transplant patient gets sick, it is a much more complex and serious situation than for the general population.

"There is not a lot of certainty but, when you are successful, it is very rewarding," says Chris.

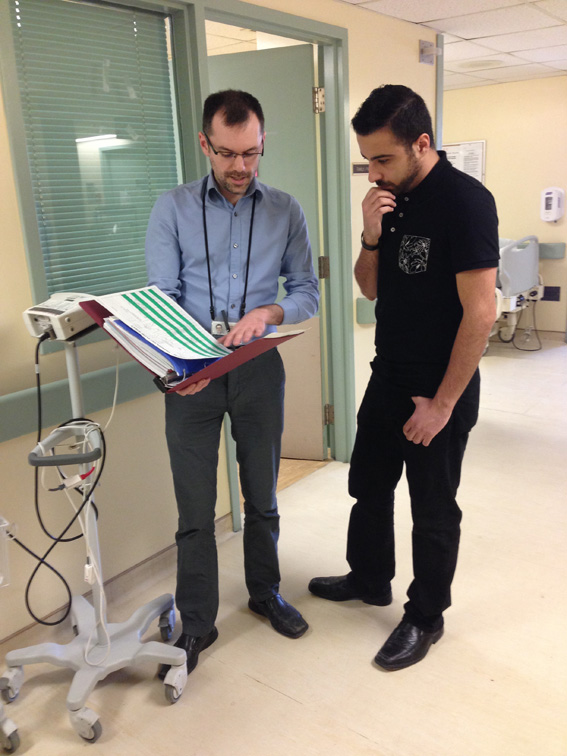

Chris often has pharmacy students working with him. His is a unique area of pharmacy practice, there are only a handful of pharmacists in Canada who have a practice solely devoted to transplant patients and the specifics of his area of practice are not taught in pharmacy school, so he is happy to share is knowledge and experience with students entering the profession.

"I taught myself," says Chris.

Whether it was a autoimmune disease, an injury, a toxicity, or a physical problem with the organ, all underlying causes for the need for organ transplants can bring surprises. Chris rises to the challenge.

"It's very dynamic," says Chris. "I never know what is going to happen."

Pictured is Pharmacist Christopher Daley and Dalhousie pharmacy student Peiman Sadeghi